Shieldwall.

Wolves Upon the Coast might be the best thing anyone has written as a part of the "OSR" movement. In many ways, playing it and subsequently reading through a lot of it has changed how I look at old school games, original D&D, and hexcrawls. You should buy it and run it for your table immediately.

Shieldwall originally came about as a set of houserules for my own home game of Wolves, in which I was a player. Our party had split, with one group doing anything they could to enable a would-be uniting conqueror, and the rest of us trying to help prepare disparate magnates and druids for war. This obviously called for mass combat rules.

There were a few options we discussed for this; the initial suggestion was Chainmail but this never materialised and I can only assume, having read Chainmail, that this is because it's difficult to read and frankly adapting it to translate the peculiarities of Wolves requires quite a lot of effort on the referee's part, and my referee had a lot of important projects on the go at the time. We talked a little about the OED Book of War, but after game sessions became more and more procrastinatory, I decided to write a battle game designed specifically for Wolves that did to Chainmail what Wolves did to OD&D.

The skeleton of the battle game was Wolves itself - Luke Gearing's original rules contain a bunch of implications and assumptions about how mass combat would work in this specific reimagining of OD&D and its setting. The plan was for Chainmail to be the flesh on these bones, but it wasn't as simple as that primarily because once again the inner systems of Chainmail just don't have the same design philosophy as Wolves, and consistency betwween Wolves and Chainmail in terms of design and game feel was really my sole most important goal.

Reading Chainmail, the need for a hack is more obvious than ever. I'm sure some high Gygaxian true believers will disagree with me here, but despite his historic game design, Chainmail is a great example of Gary's total inability to write a book. The game that comes through all this nonsense is perfectly serviceable though. The Fantasy supplement makes the same assumptions as to how heroic fantasy combat might work as D&D, which means the Hit Die can be used as a primary definition of units and characters just like it is in Wolves. The rules do indulge far too much in E.G.G.'s propensity to spin a baroque web of edge cases and exceptions, best exemplified by AD&D, which results in clashes feeling like dispassionate spreadsheet equations.

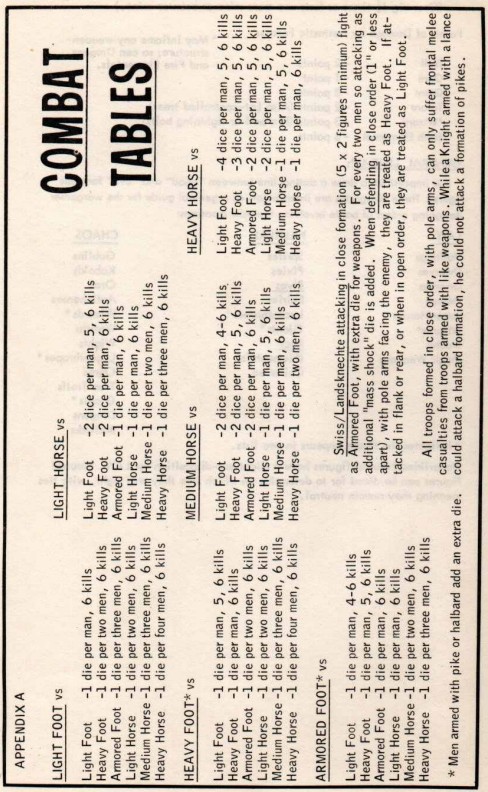

You cannot earnestly tell me this was the best way to convey this information.

Tables like this were my main starting point - the things that make you more likely to hurt someone in Chainmail are basically the same as those in D&D, with a couple of other factors like flanking and cavalry thrown in that aren't really relevant to a man-to-man combat system. I already mentioned how Chainmail's equations indulge in a lot of arguably silly edge cases, but these are also mostly present in OD&D (such as certain weapons having different properties against large targets) and are ditched by most good hacks, including Wolves. This guideline plus my existing design sensibilities let me choose what factors in combat to keep when trimming the fat.

I also decided to individualise combat results and use a "bucket of dice" attack resolution system, because I've been playing Warhammer for a decade and a half and it's wetter, bloodier, pulpier, and altogether more fun to play like this. Chainmail also does this and I think it's one of its best traits that sadly basically all mass combat systems ditch in favour of single unit-VS-unit rolls that feel a lot more like cold mathematical calculations. In a game like OD&D (or Wolves), there's a visceral quality to rolling a good hit. A target with 1HD (ie basically all normal people) is quite likely to be straight up killed immediately. This is basically the least original observation ever written on a gaming blog, and is in fact one of the most praised aspects of these games. I wonder if we'd feel the same if, with identical underlying mathematics, every fight in an RPG was a mathematical function that boils down to a single roll. The bucket of d6s, though it at first seems unwieldy, preserves the feeling of meat meeting metal far better than a single d20 would've done, and not only is it not more complex, the condensing of possible outcomes from 20 to 6 means a lot less pissing around with modifiers.

In any case, there's my incredibly indulgent retrospective of the design of this humble little supplement. I've heard of a few people playing it and enjoying it, and I couldn't be happier about that. I'd really love anyone who's played it to let me know how they found it!